Anxiety and Conditioning

Anxiety that is produced as a result of an actual situation (e.g. being in the dentist’s chair getting a tooth drilled) can become associated to events that surround the incident even when the component that originally activated the fear (a noisy drill that results in pain) is no longer present. For example, just sitting in the dentist chair while having fluoride treatment may end up evoking the same level of anxiety as when having drilling done. This process is known as conditioning.

Conditioning is a type of learning process in which the person is conditioned to think or learns to associate the painful drill with, for example, the dentist chair or with the dentist’s office or maybe even with the suburb in which the dentist’s practice resides. In such cases fear ends up being evoked by the chair or office or related suburb in the absence of any tooth drilling.

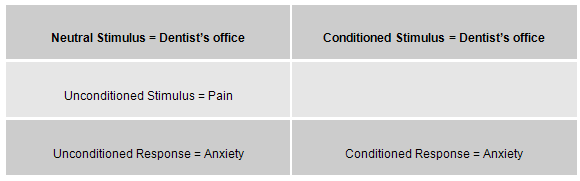

Such conditioning, known as classical conditioning, was first demonstrated by Pavlov and is defined as being the repeated pairing of a neutral stimulus (e.g., a stimulus which by itself has no real meaning or is neutral, for example the dentist’s chair, dentist’s office or dentist’s practice location) with an unconditioned stimulus (e.g., a stimulus which has meaning naturally or innately in its capacity to produce a response, for example pain).

The unconditioned stimulus of pain might end up producing a response of anxiety because of the pain experienced. The two stimuli of 1) the dentist’s chair, dentist’s office or dentist’s practice location and 2) pain, end up being associated in a person’s mind when the neutral stimulus becomes conditioned to (or is learnt to be associated with) the unconditioned stimuli.

In this case, the person would now associate the neutral stimuli of the dentist chair, dentist office or dentist practice location with pain thereby potentially being at risk of experiencing anxiety in anticipation of the pain when entering the dentist’s practice location, the dentist’s office, or the dentist chair, even if pain was no longer the result (click to see figure below).

The original and most famous example of classical conditioning involved Pavlov’s dogs. During his research on digestion, Pavlov noticed that his dog salivated in the presence of meat powder, but later began to salivate in the presence of the lab technician who normally fed them. From this, Pavlov predicted that if a particular stimulus in the dog’s surroundings was present when the dog was fed, this stimulus would become associated with food and cause salivation on its own.

Pavlov began to use bells to call the dogs at mealtime and, after a few repetitions, the dogs began to salivate in response to the sound of bells. Consequently a neutral stimulus (the bell) became a conditioned stimulus after being consistently paired with an unconditioned stimulus (meat powder). Pavlov called this learned relationship a conditional reflex, now known as a conditioned response (Lavond, & Steinmetz, 2003).

Another form of conditioning is referred to as operant conditioning (or learning theory). This was developed by Skinner and involved the use of consequences to modify behaviour. Operant conditioning is distinguished from classical conditioning in that it deals with the modification of voluntary behaviour through the use of consequences, while classical conditioning focuses on the conditioning of reflexive or innate behaviour that occurs under new conditions (Domjan, 2003).