Critical and Creative Thinking

In the 21st century, changes in society, economics, business, technology, science and the workforce are so rapid that many of the skills you learned in school or university will be obsolete shortly after you enter the workforce. Furthermore, unlike our parents who may have had two or three jobs in the same industry throughout their lifetime, today’s workforce is expected to work longer and have many more career changes throughout their lives. Therefore, in response to this, at the turn of the 21st century, many governments, business leaders, academics and educators chose to focus on investigating which skills would be required to adapt to these rapid and frequent changes.

The resulting skills are commonly known as 21st Century Skills and while there appears to be some variation, almost every list of 21st Century Skills seem to include both critical thinking and creativity. Experts agree that, regardless of what happens in the future, how technology, the economy or the global political climate might change or what industry you work in, critical and creative thinking are both important key skills that workers and leaders would benefit from in relation to adapting to such changeable working platforms.

In this article, we will briefly unpack these two crucial skills. We will also discuss some of their benefits, how they can be used both personally and professionally as well as their potential to improve your own thinking abilities.

Creative Thinking

When you hear the words ‘creative thinking’ what is the first thing that comes to mind? For many of us, our mind goes immediately to things like music, painting, creative writing and other forms of artistic expression. Creative thinking is actually having the ability to look at problems or situations in new ways in order to come up with original solutions. It might involve painting a masterpiece or coming up with an original piece of music – this list could be seen as somewhat endless. Additional examples could involve looking at problems through a different lens or from a different perspective, seeing problems as opportunities for change or growth, examining and reimagining existing solutions, coming up with new solutions, combining existing ideas to come up with something new, coming up with and testing theories and ideas and so much more. To use an old cliché, creative thinking could be seen as thinking ‘outside the box’.

Many people also believe that you are either born with or without natural creative talent and that this cannot change. From childhood, many of us are taught to believe that we are either creative or not, this is similar to perceptions surrounding mathematical, scientific, public speaking and sporting abilities as other examples. However, recent scientific findings have shown this old way of thinking to be, in fact, inaccurate. Just like weights can be lifted to strengthen muscles and jogging is known to strengthen the heart and lungs, the brain is also able to be ‘exercised’ through deliberate practice.

People who believe this to be true are considered to have a growth mindset, such an approach is believed to be able to improve one’s intelligence, memory, mathematical and creative thinking abilities… just to name a few. Living life with a growth mindset is seen as important in being able to attain a higher level of understanding in relation to any of the previously mentioned areas of expertise or fields or as a means of achieving any further progress in relation to any personal characteristics. It is thought, that if you truly do not believe in your ability to improve personal creativity, the motivation to make such improvements will simply not be there.

Creative Problem Solving

It is often assumed that if an individual is not working within a creative field, then creativity must not be important to that individual. However, as we have already established, creativity is actually an essential component of problem solving – something that we are all required to do in both our personal and professional lives. On top of this, creative thinking is also highly adaptable and transferrable, it increases innovation, efficiency and productivity and is also known to improve workplace culture.

One of the most valuable applications of creative thinking is problem solving. As you may or may not know, problem solving is not just cleaning up after something has gone wrong. It is in fact a highly creative process of coming up with new and innovate ideas and solutions. The extract below describes a helpful mnemonic for the creative problem solving process.

I. Identify the Problem: What is the real question we are facing?

D. Define the Context: What are the facts that frame this problem?

E. Enumerate the Choices: What are plausible options?

A. Analyse Options: What is the best course of action?

L. List Reasons Explicitly: Why is this the best course of action?

S. Self-Correct: Look at it again … What did we miss?

(Gueldenzoph Snyder & Snyder, 2008)

We all know the tried and true creative problem solving strategies such as brainstorming, mind-mapping and the six thinking hats by now. These techniques are classics for a reason – because they are known to work! However, instead of rehashing these old favourites, let us look at some lesser known, evidence-based techniques for creative problem solving which are not yet as familiar:

Restating the problem: This process involves re-presenting the problem in as much detail as you can both verbally and visually in a way which integrates your new knowledge about the problem with your existing understanding. Research has shown that this stage is especially effective when restatements focus on processes and restrictions in the problem (Vernon, Hocking and Tyler, 2016).

Analogical thinking: This technique involves identifying the similarities between two things in order to infer further similarities (Kupers, 2012). Research into creative thinking has found that when people are first asked to find the similarities and differences within a category, they are then able to come up with more original ideas of their own. In other words, when people use analogies or similarities to organise information, they are better at combining concepts in order to come up with more unique new ideas. Other studies have found that people come up with more original stories when drawing from more diverse concepts and people with a better ability to combine concepts come up with better solutions to problems (Mumford, Medeiros & Partlow, 2012).

Assumption reversal: Many creative thinking techniques focus on paradoxes and juxtapositions as a way of opening the mind to new possibilities. Many creative pursuits rely heavily on juxtapositions such as comedy, visual art and fiction (Cox, 2012). Many of the assumptions we hold are outdated, misplaced or untrue and can be a barrier to creative idea generation. To implement this strategy, we identify any assumptions held about a problem, reverse every assumption and use reversals as a stimulus for new ideas (Vernon, Hocking and Tyler, 2016).

Checklisting/Forced Fitting: This technique involves coming up with a set of ideas which fit into a randomly generated list of stimuli in the form of words or pictures. This process of finding links between divergent ideas, similar to analogical thinking, has been shown to improve conceptual combinations and lead to more creative idea generation – especially when the stimuli have no obvious relationship to the problem (Vernon, Hocking and Tyler, 2016).

Forecasting: Forecasting involves predicting the future consequences of an activity including positive and negative outcomes, possible errors and potential obstacles. In a study involving creative advertising campaigns, it was found that when more in depth forecasting was done during the idea evaluation and implementation planning stages, more original and effective advertising campaigns were produced (Mumford, Medeiros & Partlow, 2012).

These are just a few creative problem solving techniques that you may have not heard of before.

Critical Thinking

Like creativity, critical thinking (sometimes referred to as critical evaluation) is a key higher order thinking skill. Lower order thinking skills are those that involve simple processes such as taking in information, remembering it and regurgitating it. Higher order thinking skills on the other hand, involve transforming information using one or more complex mental processes and generating new information or making decisions.

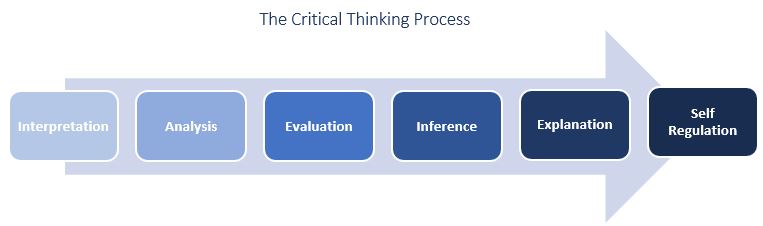

Critical thinking involves taking in information, understanding it, asking a range of questions in order to evaluate or judge the value of the information and then making a final decision. When critically evaluating information, you are identifying key points, assessing evidence, evaluating arguments and identifying and evaluating information sources. The following diagram (adapted from Ellerton, 2015) describes the ongoing critical thinking process and clearly distinguishes between lower order stages such as interpretation and higher order stages such as inference and self-regulation.

Critical Thinking Questions

While critical thinking is a complex process, it can essentially be boiled down to asking the right questions at the right time. A simple Google search will provide you with hundreds of examples of critical thinking questions. Below we have compiled a list of helpful critical thinking questions based on Ellerton’s model above, to help guide you through each stage of the critical thinking process.

Interpretation

- How can I categorise my information?

- Do I understand all of the terms in this information?

- What is the intended meaning, are terms used literally or figuratively?

- Have I clarified any possible confusion?

- Have I retained the meaning of the original information?

Analysis

- What investigation procedures were used?

- What key concepts and structures exist?

- What are the main arguments being made?

- What type of arguments are being made (refer to previous section about logic)?

- What supporting evidence is there?

- Would a diagram make this argument clearer?

Evaluation

- Is the evidence presented in context?

- Is the link between the evidence and the argument clear?

- Are the arguments valid, strong and/or cogent?

- Are the claims clearly synthesised?

Inference

- What type of evidence was used?

- What different alternative solutions can be identified?

- What evidence is there for each alternative solution?

- How did I get from the evidence to my conclusion?

Explanation

- What are my results, findings, recommendations?

- Are they clearly articulated, would a diagram help?

- Have I used the correct terminology?

- Have I justified my results using examples?

- Have I included any relevant supporting data?

- Have I represented my findings accurately?

Self-Regulation

- Am I being overconfident?

- What are my own and others’ opinions or biases?

- What assumptions have I made?

- Have I considered all the possible options?

- Have I considered all possible alternatives?

- What thinking strategies have I used?

- Have I identified and corrected any errors?

Another quick and easy way of ensuring that you are thinking critically when evaluating information and making decisions, is to use a mnemonic device. The following aptly named device is known as the CRAAP test and is used to determine whether a source of information is reliable or not.

Currency: This is to determine when the information was created. Ask yourself: What is the copyright, publication, and/or posting date? Is the information outdated for the research you are doing? Does the date matter to your research?

Relevance: This is to determine whether the information is applicable to your research. Ask yourself: For what audience was this information written (e.g., the general public, experts, scholars)? At what level is the information presented (e.g., elementary level, intermediate level, more advanced level)? Consider whether you would use and/or quote the information in your research.

Authority: This is to determine if the information you retrieve has been created by a reliable source. To decide on authority, ask yourself: Who are the authors or sources of the information? Are they experts? Are they credible? Does the author(s) provide evidence of professional affiliation(s) (such as being on faculty at a university, or a member of a professional association)? Review the credibility of the institution or organization. Is it a real, bona fide institution? Remember that any person and any organization on the internet can claim expertise. If you have any questions about the authority of a source, do some more research to find out if the author or source is, in fact, an authority on the topic(s).

Accuracy: With the prevalence of “fake news” today, it is important for you to determine whether the information you find is correct, truthful, and can be considered reliable. Ask yourself: What kind of language is being used? Is the tone of the text, images, or other material subjective, emotional, or professional?

Purpose: This is to discover what the main purpose of the information is. Ask yourself: Why does this information exist? Is it to share research and new knowledge? Is it to educate, to persuade, or to entertain? Consider the affiliation of the author(s) and the organization(s). Do their connections slant the information and point of view presented?

(Staines, 2019)

Barriers to Critical Thinking

While we all like to believe that we can think clearly and critically and are not vulnerable to thinking traps or manipulation, the fact is that despite our best efforts, there are a number of barriers that often impede critical thinking. In her book on critical thinking skills, Cottrell (2017) identifies several common barriers or impediments to critical thinking. As you read through this list consider any times throughout your life when you may have fallen into one of these common traps.

Misunderstanding: Many people incorrectly assume that critical evaluation involves criticism, others may be hesitant to engage in critical evaluation because they feel that it is hurtful or negative. However, critical evaluation involves identifying both positives and negatives, and can lead to positive outcomes by helping us and others to improve (Cottrell, 2017).

Over confidence: The Dunning Kruger effect (a common cognitive bias or thinking trap) leads many of us to overestimate our own intelligence and abilities, including our ability to critically evaluate. Humans are hardwired to make our lives easier by relying on cognitive shortcuts like heuristics and biases, especially when we are not paying close attention. We may also find ourselves making weak or invalid arguments if we are not actively engaged in critical thinking (Cottrell, 2017).

Lack of skill: Despite our best intentions, some of us may not yet have the skills, knowledge and strategies required to engage in high level critical thinking. However, as we know, it is possible to improve our critical thinking skills (just like any other characteristic) if we take the time to practice them (Cottrell, 2017).

Deference to experts: Unless you are an expert in your field, many of us feel like we are not knowledgeable or qualified enough to critique experts or those more qualified than us for a number of reasons. Regardless, as we already mentioned, critical analysis involves positives and negatives, helps us and others to improve and any expert worth their salt should welcome constructive critical analysis (Cottrell, 2017).

Feelings and Emotions: Often times what we hear or read when performing critical analysis can contradict our own strongly held beliefs or opinions. This kind of cognitive dissonance may provoke an emotional response which clouds our ability to think clearly and critically. Critical thinking does not necessarily mean that you must abandon your beliefs, it simply means that you must critically analyse the evidence which supports your own and others’ points of view (Cottrell, 2017).

Lower order thinking: Unfortunately, despite our best efforts, many of us fall into the trap of relying on lower order thinking skills and neglecting critical thinking. While the ability to take in and remember information is important it does not replace the need to critically evaluate that information in order to gain deeper understanding (Cottrell, 2017).

Laziness: One of the barriers to critical thinking that may lead to some of the other barriers identified above is a lack of focus and attention to detail. Critical analysis is hard work and it cannot be rushed (Cottrell, 2017).

As you have hopefully learned through reading this article, critical and creative thinking are and will continue to be some of the most valuable and sought after skills in the 21st century. Despite some common misconceptions, as discussed, both of these crucial skills can be developed and improved throughout the lifespan, even into adulthood. All that is required to do this is a growth mindset and practice.

We hope that this article has given you a brief introduction to some of the benefits of critical and creative thinking, strategies to use in your personal and professional life and some common pitfalls to look out for. If this article has sparked your interest in critical and creative thinking, consider undertaking some additional reading on logic, reasoning and how to overcome cognitive bias.

References

- Cottrell, S. (2017). Critical Thinking Skills: Effective Analysis, Argument and Reflection. London, UK: Pelgrave.

- Cox, D. (2012). Creative Thinking for Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Ellerton, P. (2015). The Critical Thinking Matrix. Retrieved from: Website.

- Gueldenzoph Snyder, L. & Snyder, M. (2008). Teaching critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Delta Pi Epsilon Journal, 50(2), 90-99. Retrieved from: Website.

- Kupers, W. (2012). Analogical Reasoning. In N. Steele (Ed.). Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Retrieved from DOI.

- Mumford, M. D., Medeiros, K. E., & Partlow, P. J. (2012). Creative thinking: Processes, strategies, and knowledge. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 46(1), 30–47. Retrieved from DOI.

- Staines, G. (2019). Social Sciences Research: Research, Writing, and Presentation Strategies for Students (3rd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Vernon, D, Hocking, I & Farahar, C. (2016). An Evidence-Based Review of Creative Problem-Solving Tools: A Practitioners Resource. Human Resource Development Review, 15(2), 230-259. DOI 10.1177/1534484316641512.