Self-Awareness, Emotional Regulation and Empathy

How accurately can you predict how you come across? Are you good at picking up how you are feeling and how this affects those around you? How well do you consciously know and understand yourself including your feelings, wants, goals, desires and motivations? Self-awareness is paramount to Emotional Intelligence (EI) and Emotional Regulation (ER) and is commonly defined as the understanding of our thoughts and emotions. It also includes an understanding of how these thoughts and emotions influence our behaviours, ourselves and those around us.

What is Emotional Regulation?

Emotional regulation, in its most simplest form, is the ability to exert control over one’s own emotional state. Described as “the processes by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express these emotions” (Gross, 1998, p. 275), ER is closely linked in with self-awareness. Self-awareness relies on the person being in tune with how they are feeling and understanding what is causing the emotion. ER then takes it a step further and looks at how, and when, the person should display those emotions.

It is important to note that historical research conducted on emotions often looked at the idea of suppression of emotions in the workplace, rather than the regulation of these emotions. Grandey’s (2000, pp. 98-100) article on emotional labour provides a quick introduction into this research with their discussion of emotional labour. They then provide a more modern perspective on emotions at work by looking into emotional regulation and the different theories relating to it. These theories look at changing, supressing or regulating emotions to reach workplace goals. It is important to remember that ER is not used to suppress emotion, but rather about the management of emotions to reach desired goals.

Example:

You are driving home after picking up your child from school. You are both chatting and feeling quite relaxed. As you are trying to merge onto the motorway, someone cuts you off causing you to nearly crash into the barrier next to you. You feel scared.

How do you react?

- You honk at them, wind down the window and yell obscenities at them. You then turn to your child and notice they look frightened and say, “What an idiot! He scared us both!”

- You say nothing but continue to dwell on it all evening. You continue the rest of your car ride with your child but constantly make comments about how people drive on the road and generally feel annoyed and angry but act as if nothing happened.

- You feel angry and take a quick breath. You turn to your child, who looks frighted and say “hey that was quite scary! That frightened me too.”

- Which option do you think is the best one to take?

- Which option do you normally take?

- What do you think is the outcome of each option, including the impact it had on the child in the car?

In both option A and C, you are showing a certain level of self-awareness by naming how you are feeling. However, only option C shows good emotional regulation where you were able to express how you felt and do it in the way that was appropriate for the context and situation. Option B shows an example of emotional labour and suppression. Here you are both denied the feelings that you went through as well as failed to engage in any useful actions. By putting on the ‘everything is ok’ act and supressing your emotions, the result was both emotionally and personally draining.

The suppression of emotions is rarely healthy and can often result in negative outcomes, lack of true connection and health concerns both in physical and psychological health (Grandey, 2000; Salovey, 2001). If applied correctly, ER can actually help with stress reduction, better health and increased confidence (Salovey, 2001). Emotional regulation can also be seen as the ability to confidently identify emotions, how they relate to the situation at hand, and then assisting in identifying which might be the best approach in expressing them.

Salters-Pedneaul (2019) explains the Process Model for Emotional Regulation including how to use ‘SAAR’ (Situation, Attention, Appraisal, and Response) in your everyday life.

Example:

You are at a family gathering when the conversation starts turning political. In the past, tempers usually start to flare and people may get into heated arguments. You don’t really wish to take part in this.

Situation-

Taking steps to influence the situation in which you are in or taking steps toward changing the situation e.g. deciding to go say hello to the kids or grab another drink/offer to get a drink for the table.

Attention-

Consciously and selectively choosing where to direct your attention e.g. choosing to look at the footy game on TV instead of listening to the political conversation at the gathering.

Appraisal-

Cognitively reframing the meaning you are giving to a situation e.g. deciding that the political conversation at the dinner table is an opportunity to hear the thoughts of other people instead of thinking it is a direct attack on your own opinions.

Response-

Modulating or influencing your emotions as well as how you respond e.g. normally you would get into an argument and feel angry for the rest of the day, but in this case you choose to regulate your emotion and acknowledge that you are becoming frustrated and choose to not respond to the conversation or simply remind yourself that this is just a sharing of ideas.

This Process Model is a useful tool to keep in mind. Within this model and in the article, you can see how much power you actually have to choose your response; be it within a situation, how much attention you pay to it, how you assess (appraisal) what is happening or how quickly you respond. A small caveat in the appraisal side of this model – use your self-awareness to check in with yourself and ensure you are not overthinking the situation or making a decision based on anxiety/fear or jumping to conclusions.

Understanding Empathy

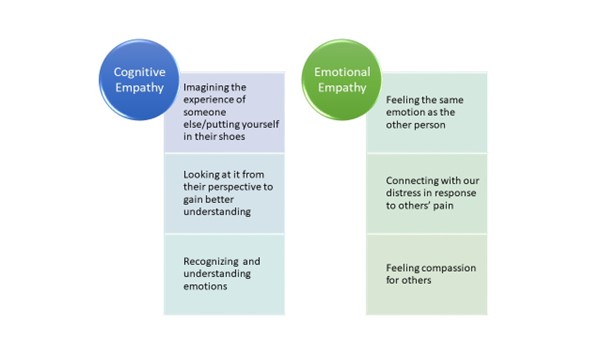

Empathy fuels authentic connections between individuals. The diagram below shows a visual representation of the two most common types of empathy that people (and leaders) can engage in:

Please take a moment to reflect a time at work, study or in a social gathering where you were having a tough time. For example, you may have received some bad news, may have been experiencing some relationship concerns or perhaps you were struggling with a personal dilemma.

- Can you remember what were some of the useful, or not so useful, supports that you received? Write down some of the things which you found useful, including comments that were made.

- Take another minute to remember if you spoke to anyone and felt that they actually understood? How did you feel when this occurred?

- If there was a time you have felt understood, do you remember how this person was able to connect with something within themselves in order to validate your emotions? Write down what they did and ways that you may wish to replicate this.

If you answered yes to the last questions, you may have experienced someone sharing empathy with you.

Empathy is defined as the ability to sense the emotions that other people are feeling, combined with the ability to imagine or understand what someone else maybe thinking, feeling or going through. As a biologically rooted ability in all humans, empathy can help us to build successful relations by increasing mutual understandings as well as through enabling the vision of differing perspectives, needs and intentions of others (Greater Good Science Center, 2021).

Empathy should not be confused with sympathy. Sympathy relates to the sharing of feelings of sorrow, pity or compassion with others – but it does not mean you understand or know what it may be like to be in their shoes. Empathy on the other hand, requires a person to connect with something within themselves to really understand, or even begin to imagine, how it may feel to be in that position. Brené Brown, a leading researcher in empathy, describes empathy as a skill that can be strengthened with practice and states that “Empathy fuels connection, and sympathy drives disconnection” (2020).

Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from the AIPC’s Upskill on Emotionally Intelligent Leadership.

References

Brown, B. (2013, December 10). RSA short: Empathy. Brené Brown. https://brenebrown.com/videos/rsa-short-empathy

Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of occupational health psychology, 5(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.95

Greater Good Science Center. (2021). What is empathy? Retrieved from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/topic/empathy/definition

Gross, J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271-299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

Kellett, J. B., Humphrey, R. H., & Sleeth, R. G. (2002). Empathy and complex task performance: two routes to leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(5), 523–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00142-X

Salovey, P. (2001). Applied emotional intelligence: Regulating emotions to become healthy, wealthy, and wise. In J. Ciarrochi, J. P. Forgas, & J. D. Mayer (Eds.), Emotional intelligence and everyday life (pp. 168-184). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Salters-Pedneaul K. (2019). How Emotion Regulation Skills Promote Stability. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/emotion-regulation-skills-training-425374